Mechanical stratigraphy in Scotland’s Geology & beyond

What is mechanical stratigraphy

Fractures in the plunge area of the Khaviz anticline, Iran - showing higher intensity of fractures in thinner beds than in thicker beds. From Ole Petter Wennberg.

Put simply, thinner beds (of e.g., sandstone) often have more fractures than do thicker beds - an example is given opposite.

Also, certain types of rocks are more susceptible to fracturing than others - for example, brittle rocks like dolomite are often more fractured than rocks such as limestone which may be less brittle.

These types of rules make it easier to predict the distribution of rock fractures in the subsurface - particularly when our windows into the subsurface (seismic and well logs) are limited in resolution and area sampled. Outcrops are valuable here as provide the opportunity to see how fractures are distributed in 3D and what sort of drivers influence their distribution.

Layer Thickness

Often, thicker layers will have less fractures (greater spacing) than thinner layers e.g., the observations by McQuillan [1] on some Zagros anticlines in Iran.

A nice example of this from the Khaviz Anticline in Iran is shown above right. We can explain this by the assumption that the width of the stress shadow (release of energy during fracturing) is a function of the height of the fracture. Taller fractures cast a wider stress shadow, forcing fractures to form at a wider spacing in thick beds.

Rock Type

In the outcrop (below left) the dolomite on the right hand side is pervasively fractured, whereas the limestone on the left hand side is unfractured. In another example from the same locality, dolomite infills burrows (darker grey patches) and is fractured, then cemented (small white streaks). The background limestone (lighter grey) is unfractured. See Fig 3-5 of Nelson (2001) which shows higher fracture density in dolomite than limestone. This is because dolomite is brittle.

Cupido Platform Carbonates (E Cret), Las Palmas Canyon, Mexico; unfractured limestones on the left, fractured dolomites on the right of the limestones. On the right hand photograph, only the burrows infilled by dolomite are fractured - the background limestones is unfractured.

Scottish Examples

The exposures below are from a coastal section of Carboniferous age geology to the East of the town in St Andrews in Scotland. Note how the thick sandstone bed in the upper part of the outcrop has little/no fractures whereas the thinner sandstone beds are fractured. In this case these fractures are likely to be joints are they are near vertical and don’t tend to offset the bedding. The shales are less fractured than the sandstones as the ductile shales are more difficult to fracture. Therefore, mechanical stratigraphy is controlling occurrence of fractures in this outcrop.

Interbedded sandstones and shales, E Beach St Andrews, UK. The sandstones are more highly fractured than the shales (some are shown with red lines on right hand side).

The view (from the same area) clearly shows jointed sandstones although the shales also appear to have fractures albeit at smaller scale.

Dipping sandstone beds encased in shales; note the high intensity of fractures in the sandstone

In Carbonate Rocks

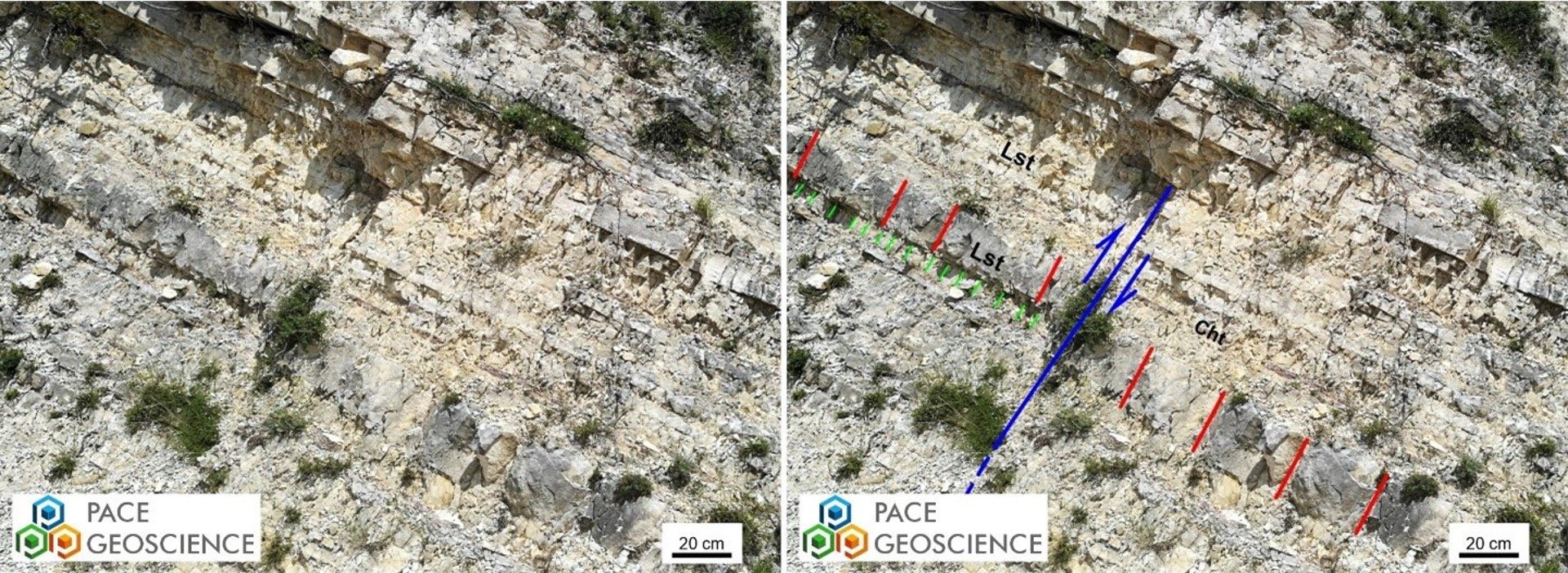

Our outcrop example of interbedded limestones and cherts (below) shows a major contrast in the distribution of fracture intensity within package. Each layer interface represents a sharp discontinuity that marks a lithological change acting as a mechanical boundary for fracture propagation. In such a mechanical pattern, fractures (mostly joints) are prone to be bed-confined and the fracture intensity and distribution are a function of the mechanical properties of the different carbonate layers.

Thicker coarse-grained limestone (calcarenite) beds have a lower fracture intensity (red lines) than the thinner fine-grained limestone (micrite) beds (green lines). This is particularly the case when these beds are adjacent or interbedded with chert layers or lenses. Also shown is a throughgoing fault (blue), which we interpret as a tilted syn-sedimentary normal fault (note bed thickening to the right).

Interbedded limestones and cherts (Pennapiedimonte, Italy) of Upper Cret. age; the thinner micritic limestone beds are most fractured. Outcrop example from the Majella anticline in the foreland fold-and-thrust belt of the Central Apennines, a world-class analogue for the study of fractured carbonate reservoirs.

This figure features in the “nothing beats the field” series in GeoExpro magazine https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7196415896175706113/

Another example of mechanical stratigraphy - this time from Zechstein carbonates of Marsden Bay in NE England - is shown on an exposure of different carbonates below. The limestone (grey unit at bottom) and the laminate unit directly above it are unfractured. Only the thin turbidite layer in the middle of the view is fractured - here we can say that they are bed bound.

Bed bound fractures in dolomite (brown coloured rocks, the limestones are grey coloured). The laminated unit above the limestone (at bottom) is unfractured. This is overlain by unfractured turbidites. The thinner turbidite layer above is heavily fractured.

[1] McQuillan, H. 1973. Small scale fracture density in Asmasri Formation, southwest Iran and it’s relation to bed thickness and structural setting. AAPG Bulletin, 57, 2367 - 2385.